Poker & Pop Culture: The Long, Strange Life of the Dead Man's Hand

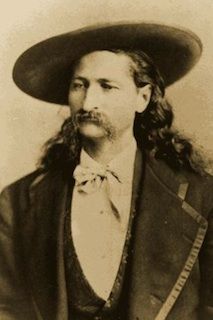

This week we conclude our survey of "saloon poker" with some consideration of the most famous hand ever played in a saloon, the last one ever played by James Butler "Wild Bill" Hickok �� a.k.a, the "dead man's hand."

"I'm Sort of Public Property"

Hickok was a well known figure for several years prior to that fateful August afternoon in Nuttal & Mann's Saloon No. 10.

Born in Illinois in 1837, by his late twenties Hickok had already collected a number of adventures, including enduring a bear attack, working with the Pony Express, and serving the Union Army in various capacities during the Civil War.

He'd also been involved in a couple of shootings, most notably the first widely reported "quick draw" duel in which he killed a man named David Tutt following a dispute about poker debts (and, likely, a woman).

In the fall of 1865 �� not long after the Tutt duel �� Hickok's notoriety had grown enough to earn him a visit from journalist George Ward Nichols.

Later, in the February 1867 issue of Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Nichols would tell Hickok's story to a national audience, going to great lengths to present Hickok as some sort of gunslinging god among men.

Upon meeting Hickok, Nichols sketches him as the epitome of rugged, Old West manhood, possessed with the "handsomest physique I had ever seen" and "a singular grace and dignity of carriage." Nichols seems spellbound by Hickok's appearance, describing his eyes as "gentle as a woman's."

Continuing his impression of Hickok, he even suggests "the woman nature seems prominent throughout" �� until, that is, Nichols remembers that "you were looking into eyes that had pointed the way to death to hundreds of men."

In case you missed that, Nichols repeats it.

"Yes, Wild Bill with his own hands has killed hundreds of men. Of that I have not a doubt."

It's an exaggeration, of course, not unlike the fabricated story about Bat Masterson having killed 26 men by the age of 27 published a few years later in the New York Sun.

Such hyperbolic tales of "Wild West" figures were popular, though, in post-Civil War America, often creatively enhanced by audience-seeking journos like Nichols.

Nichols briefly relates the story of the shootout with Tutt, then asks Hickok if he himself ever felt fear. Hickok admits he has. "They may shoot bullets at me by the dozen, and it's rather exciting if I can shoot back," Hickok explains. "But I am always sort of nervous when the big guns go off."

A demonstration of Hickok's skill with a pistol follows, then Nichols wraps up his report noting "it would be easy to fill a volume with the adventures of that remarkable man." Before departing, Nichols asks Hickok if he might be permitted to share with the world his story.

"Certainly you may," Hickok replied. "I'm sort of public property."

Wild Bill Hickok at Cards

The Harper's story catapulted Hickok to nationwide fame, accompanying him wherever he went as he proceeded to work in various locales as a lawman. Stories of his poker games continued as well, and it was in both contexts �� as an upholder of the law and at the card tables �� that Hickok would become involved in more shootouts.

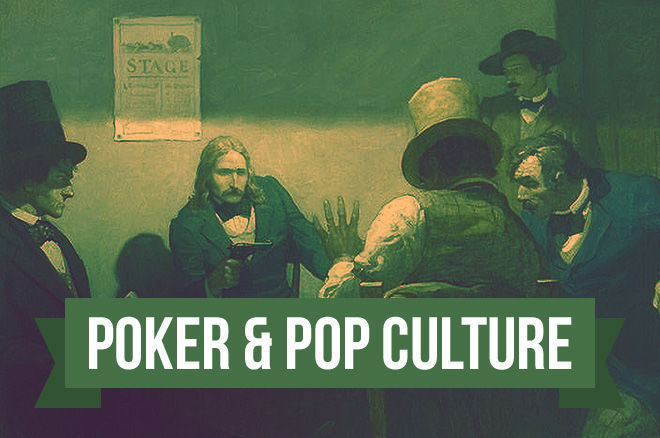

One such scene is imagined in N.C. Wyeth's 1916 oil painting of "Wild Bill Hickok at Cards" (appearing above). Another oft-repeated (and perhaps invented) story attributes a classic Old West poker line to Hickok.

While playing an opponent he suspected was cheating, Hickok called a bet and saw his opponent turn over jacks full. Hickok responded by showing his hand and declaring a winner, aces full of sixes. When his opponent saw only three aces and a single six, he objected.

"There's only one six," he said.

Hickok then pulled out his pistol. "Here is the other six," he said, and his opponent conceded the pot.

Eventually Hickok's career as a lawman would end with his losing a position as a marshal in Abilene, Kansas after accidentally shooting and killing a deputy. (Poor eyesight, perhaps caused by glaucoma, may have contributed to the mistake.)

He'd marry an older woman in Wyoming, and soon after a 39-year-old Hickok would travel to the Black Hills of South Dakota in search of gold while his new wife stayed behind in Cheyenne. He'd reach Deadwood in July, not long after another notorious Old West figure, Martha Jane Cannary, a.k.a. "Calamity Jane," had arrived. Rumors of a romance between the two (later furthered by Jane herself) were said to be unfounded.

Hickok had only been in Deadwood about three weeks when on August 2, 1876 he found himself in a poker game at Nuttal & Mann's Saloon No. 10. Some accounts say the variant being played was five-card stud, others five-card draw. At around three o'clock a man named Jack McCall stepped into the saloon and after saying "damn you, take that" fired a pistol into the back of Hickok's head, killing him instantly.

Speculation about McCall's motives have included his having lost to Hickok in an earlier game then taken offense at Hickok's loan offer afterwards, his having been under the impression that Hickok had earlier killed his brother, or his having been encouraged and/or paid by others who desired Hickok's death.

Hickok's fame likely bore some significance, too, as it surely made him a target previously both of gunslingers and card players. After a couple of trials, McCall was eventually hanged for the crime.

One oft-repeated facet of the story is Hickok sitting with his back to the saloon entrance, against his usual custom. The seat was only one available when Hickok joined the game, with a player named Charlie Rich (who would later become marshal of Deadwood) reportedly having refused a request from Hickok to switch chairs.

The other always-included detail, of course, was the hand Hickok held at the time of his death �� two black aces and two black eights. Or, as it would later come to be called, the "dead man's hand."

Dawn of the "Dead Man's Hand"

In 1926, Frank G. Wilstach wrote a biography of Hickok that provides evidence both of the hand and its having earned the nickname.

Wilstach had corresponded with Ellis T. "Doc" Pierce who had been the barber in Deadwood and was given the duty of preparing Hickok's body for burial. Pierce shared with Wilstach details of the scene, including how Hickok's "fingers were still crimped from holding his poker hand... which read 'aces and eights.'" (The image makes draw seem more likely than stud as the variant being played.) Wilstach underscores how "since that day" aces and eights was thereafter known as the "dead's man hand."

Wilstach's account via Pierce is in fact the only one from a witness that identifies the actual hand. Meanwhile there has been a great deal of conjecture about what Hickok's fifth card was, though no consensus. In his 2008 book Ghosts at the Table, Des Wilson makes an entertaining and somewhat heroic effort to pin down the fifth card, but is forced to conclude it remains a mystery.

Less well known is the fact that during the half-century between Hickok's killing and Wilstach's book, several other poker hands were known as the "dead man's hand." In 1978, Cecil Adams shared some research performed for his "The Straight Dope" column uncovering a number of references to other dead man's hands in articles and books, including...

- jacks full of tens �� Grand Forks Daily Herald, 1886

- jacks and eights �� Eau Claire Leader, 1898

- tens and treys �� Trenton Times, 1900

- jacks and sevens �� Encyclopaedia of Superstitions, Folklore, and the Occult Sciences, 1903

- jacks and eights �� Hoyle's Games,, 1907

From these intervening decades, Adams also shares a few references to aces and eights, the earliest coming in 1900. He concludes that by the time Wilstach wrote his book in 1926, even with the barber-slash-undertaker's account there's at least some doubt over (1) whether Hickok actually held aces and eights, and (2) whether aces and eights were thereafter exclusively known as the "dead man's hand."

John Wayne, Bob Dylan, and the LVMPD

Thanks to the hundreds of cultural references to the hand that have followed Wilstach's account, however, aces and eights have easily become the last "dead man's hand" standing. Or lying on the ground, as it were.

Numerous films �� some about Hickok, some not �� have highlighted the hand, including John Ford's 1939 western Stagecoach in which a character holding aces and eights is killed by the hero portrayed by John Wayne. Several television shows have incorporated references as well, as have works of fiction including several novels in a variety of genres carrying the title Dead Man's Hand.

In Ken Kesey's 1962 novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, the protagonist R.P. McMurphy is described early on as having a couple of tattoos, one being "a poker hand fanned out across his muscle �� aces and eights." (Later McMurphy will run poker games among the patients in the psychiatric hospital to which he's been assigned after faking insanity to get out of a prison sentence.)

The "dead man's hand" is a frequent reference in song lyrics, with Bob Seger's "Fire Lake," Mot?rhead's "Ace of Spades," and Bob Dylan's "Rambling, Gambling Willie" among the better known examples.

Dylan's 1963 song tells the long and winding story of a gambler named Will O'Conley who rides a lengthy winning streak before getting killed in a poker game when an opponent shoots him through the head.

It "was a tragic fate," sings Dylan, and "when Willie's cards fell on the floor, they were aces backed with eights."

There's a "Dead Man's Hand" video game set the Old West (a first-person shooter, natch). It's the name of both a Belgian-brewed stout and a Las Vegas bar. And the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department Homicide Section has even adopted aces and eights as its logo, a grim allusion to history's best known poker-related murder.

Conclusion

Just as Hickok himself recognized he'd become "sort of public property" thanks to his fame as a gunslinger, the dead man's hand has been appropriated by the public at large �� whether ironically or in earnest �� as an all-purpose method to convey ominous foreshadowing.

In terms of poker's history, the hand stands as an ultimate symbol of "saloon poker," instantly evoking both the image of the Old West cowboy and the game's frequent association with danger and violence �� a legacy that has extended well into the 20th century and still exists today.

The story behind the hand perhaps adds further nuance to the symbol, in particular Hickok being caught completely unaware, never having had an opportunity to defend himself against his murderer. If we were to extend the mythologizing of Hickok begun in Harper's Magazine nearly a century-and-a-half ago, poker becomes a fatal flaw for our "hero," the concentration required by the game �� or the exhilarating thrills it sometimes offers �� proving for him a deadly distraction.

In other words, as storytellers and others continue to wax lyrical about the dead man's hand, its endless reiterations haven't necessarily helped poker's image in the culture at large, suggesting as it does a sinister deadliness potentially revealing itself with every deal.

Photos/images: "Wild Bill Hickok, ca. 1873-74," Public Domain; "Dead Man��s Hand," cavenaghi9, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic; LVMPD Homicide Section's logo, LVMPD.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America��s Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.