Poker & Pop Culture: Gambling U.S. Grant and Reproachful Robert E. Lee

Our ongoing tour of the tables has carried us through saloons and steamboats of the 19th century. This week we turn to soldiers playing poker, specifically those of the Union and Confederate armies who in their packs carried packs of cards with which to engage in less bloody conflicts in between battles.

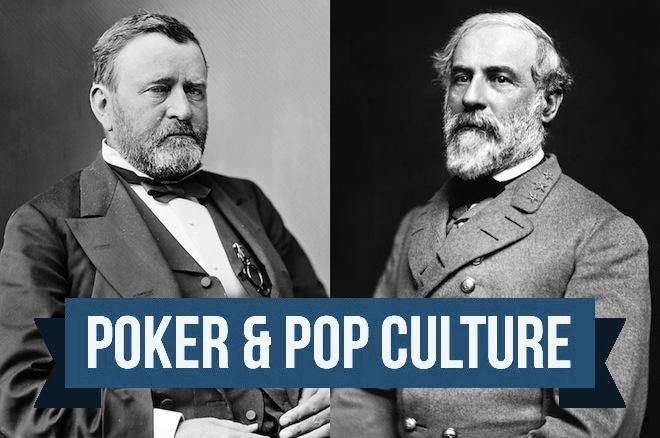

We'll start this week with the commanders �� Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee �� who perhaps unsurprisingly demonstrated contrasting attitudes towards the embattled nation's most popular card game. Then next week we'll look more closely at the soldiers' poker playing, a prelude of sorts to later discussions of poker during wartime.

Ulysses S. Grant: Glad to Gamble

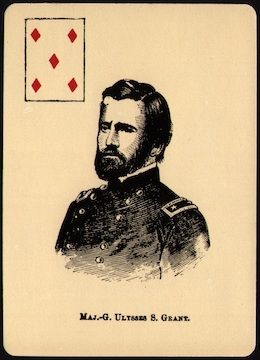

Commanding General of the Union Army, Ulysses S. Grant would later join the list of poker-playing presidents when he'd subsequently serve two terms in the nation's highest office during reconstruction. On such a list he'd join the man with whom he worked to lead the Union, president Abraham Lincoln, who likely learned the game as a young man when sailing a flatboat carrying produce from Illinois to New Orleans.

Grant was a card player from his youth right through his final years. He played while a cadet at West Point where he arrived in 1839 and graduated in 1843, despite rules forbidding (among other things) alcohol, tobacco, and card playing.

During Grant's first year there he'd join a secret group called T.I.O. or "Twelve in One," described by historian Charles Bracelen Flood as "a dozen classmates who pledged eternal friendship and wore rings bearing a significance only they knew." Among the T.I.O.'s pastimes was "a card game called Brag," one oft-mentioned as a precursor to poker.

Despite poker being a favored proclivity of Grant's, he never himself bothered to chronicle his own card playing that much. His great end-of-life autobiography, the Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant (published by the poker-proponent Mark Twain shortly after Grant's death in 1885) shares no stories of his own poker playing and only casual references to that of others. In fact, there are only a few small, mostly incidental references to cards in all 31 volumes of The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant.

Grant once mentions in a letter sending $10 to the U.S. Senator James W. Nesmith on February 14, 1867, calling the payment a "Valentine" and adding "this is the day for distributing such things." A notation clarifies the money "was a little balance on a poker transaction." Another note shares journalist John Russell Young's 1879 diary entry describing a poker game with Grant.

In the Papers there also appears evidence of Grant's notorious feud with Captain William J. Kountz, one of a few military men with whom Grant butted heads during the war. Kountz oversaw river transportation for the Union forces, and Grant's displeasure with him escalated to the point of Grant having Kountz arrested. Kountz would later file formal charges against Grant in retaliation, including famously accusing him of being a drunk.

A list of Kountz's charges appears in the Papers, and among the incidents of drunkenness listed, there's a reference to Grant "playing Cards for money while he was a disbursing Agent (disburseing secret service money)." While the episode didn't help Grant's reputation, he would be the one to ascend into prominence while Kountz would fade into obscurity.

The Papers also includes one other account of Grant's poker playing made by the journalist George A. Townsend best known for his reporting on both the war and Lincoln's assassination. Townsend shares how Grant's love of gambling games went against both his West Point upbringing and his father's wishes. "He was dumbfounded," wrote Townsend of Grant's father, "that Grant would play poker or occasionally faro."

Townsend goes on to connect Grant's poker style to his ability as a military commander, emphasizing as others would that his readiness to take risks proved especially beneficial on the battlefield.

"You know how a man of Grant's temperament would bet," says Townsend. "The first wager he made would be with all he had for all on the cloth. 'All the downs' was his favorite bet. He did the same in war.... He felt the spirit of the game and played for big victories and promotions."

Grant Picks Off Fightin' Phil's Bluff

A more explicit discussion of Grant's poker playing would finally come well after his death in 1909 via one Ferdinand Ward, the entrepreneur who partnered with Grant's son and infamously lost a fortune through corrupt financial deals that landed him six years in Sing Sing. Grant himself was ruined by the scheme, having invested heavily as well.

Well afterwards Ward shared his story, including telling of his friendship with the elder Grant which comprised the last four years of the the ex-president's life. Ward shoulders the blame for his failed racket, absolving Grant as essentially a "child in business matters" whose only role was to play the part of a ruined investor.

Of course, Grant's willingness to sink a quarter million into the venture reflected again his desire to play for "big victories," a character trait Ward emphasizes as well. "One of the characteristics of the General which impressed me most forcibly was his courage," writes Ward. "Morally and physically he was the bravest man I ever knew. I do not think he ever knew fear."

Among the stories Ward tells to illustrate such courage are a couple of their poker games "of which the General was inordinately fond."

"I think the game appealed to him because he had to bring to it many of the same qualities which caused him to be determined to 'fight it out along this line if it takes all summer,'" surmises Ward. He alludes to a much-quoted line of Grant's delivered in May 1864 just a couple of months after he had taken over command of the Union forces, underscoring his readiness to continue fighting in Virginia despite having endured casualties.

"The possibilities for ambuscades, masking of batteries and sudden sorties in the great American indoor game appealed to him immensely," Ward continues. "It had for him the same fascination which chess has had for other military geniuses."

Ward shares a couple of poker stories about Grant, with the most apt one involving a memorable hand of five-card draw. The game was five-handed, also involving Grant's friend Philip Sheridan �� a.k.a. "Fightin' Phil" �� who had served as a Union general and whose calvary played an important role in the war-ending Appomattox Campaign.

In the hand Grant draws three cards while Sheridan stands pat, and when the latter "bet the limit" everyone folds except Grant who raises. "Sheridan promptly came back with another boost, and General Grant saw that and raised again. Then General Sheridan with his pat hand called. General Grant showed a pair of nines and won the pot, as Sheridan had nothing."

With a laugh, Grant takes out his cigar and says "I knew you were bluffing, 'Phil,' and I would have kept it up until I had staked my pile."

A thoroughly impressed Ward concludes that Grant "seemed to be possessed of a sort of sixth sense which enabled him to size up situations in a flash of intuition."

Robert E. Lee: Critical of Cards

By contrast, the Confederacy's commander General Robert E. Lee was much less inclined to gamble at cards. In fact, he was fairly intolerant of poker as a character-compromising vice to be avoided at all costs.

Lee also attended West Point some years before Grant in the late 1820s, and adhered dutifully to the prohibition against card playing, earning zero demerits during his four years as a cadet. Later during an early tour of duty at Fort Monroe, Lee would observe with distaste his fellow officers' poker playing, once writing a letter to a former classmate, Jack Mackay, describing his annoyance.

"I have seen minds formed for use and ornament degenerate into sluggishness and inactivity, requiring the stimulus of brandy and cards to rouse them into action," wrote Lee.

Such antipathy toward poker found expression again many years later not long after Lee took over command of the Confederate forces in 1862. In one of his "General Orders" �� this one addressed to the Army of Northern Virginia �� Lee was entirely unambiguous regarding his intolerance of all forms of gambling, including poker.

"The general commanding is pained to learn that the vice of gambling exists, and is becoming common in this army," the Order begins. "He regards it as wholly inconsistent with the character of a Southern soldier and subversive of good order and discipline in the army."

"All officers are earnestly enjoined to use every effort to suppress this vice, and the assistance of every soldier having the true interests of the army and of the country at heart is invoked to put an end to a practice which cannot fail to produce those deplorable results which have ever attended its indulgence in any society."

Despite the order, card playing would continue to be prevalent throughout the four years of the Civil War, even when packs �� like other provisions �� became harder for the Confederate soldiers to come by (about which we'll discuss more next week).

When Sherman Outplayed Hood

Some of Lee's generals were known to enjoy poker as well, and in his Cowboys Full: The Story of Poker, James McManus compiles the stories of a few of them.

There's the brutal and odious Nathan Bedford Forrest, later to become the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. McManus tells of his card playing during the war and poker-like strategems on the battlefield, also relating how after the war Forrest played poker to earn a living despite his Christian wife's objections.

McManus also tells of William "Little Billy" Mahone, present with Lee at the surrender at Appomattox in early April 1865. After the war Mahone became an important figure during reconstruction, involved heavily in the building of railroads. Later during the 1880s he'd serve as a Virginia senator, taking part in the increasingly popular poker games played by Congressmen of the era.

However, the most interesting �� and probably most historically significant �� story of Lee's poker-playing generals concerns John Bell Hood who after being promoted commanded the Army of Tennessee during a couple of decisive battles during the second half of 1864.

While the North holding the "big stack," the war's outcome was nonetheless still in doubt, which meant Lincoln's reelection in 1864 wasn't assured either. For Lincoln to remain in office meant the Union would continue forward with the battle, though things might go differently should someone else be elected, say the Democrats' nominee George McClellan (another of Grant's antagonists).

Unlike Lincoln's party, the Dems were in favor of ending the war and settling with the Confederacy. Even though McClellan disagreed with his party's platform, it's clear that if he were to have claimed the presidency from Lincoln the country's future �� including whether or not slavery would be abolished �� would have been altered greatly.

As it happened, decisive victories by the Union during the run-up to the election assured Lincoln's victory by a wide margin. One of those victories was against forces commanded by Hood, newly appointed by the Confederacy's president Jefferson Davis to lead the Army of Tennessee into the Atlanta Campaign.

Hood's adversary was William Tecumseh Sherman and his larger Military Division of the Mississippi. Not knowing much about the young Hood, Sherman asked his officers if anyone had any acquaintance with him previously, perhaps at West Point. One stepped forward, a "pro-Union Kentuckian" (writes McManus) who informed Sherman he had seen "Hood bet $2500 with nary a pair in his hand."

Such information helped Sherman plot a strategy versus Hood, surmising that his boldness in a hand of poker might well translate to boldness on the battlefield. That meant Sherman could go on the offensive with his troop advantage and expect Hood not to retreat as he should.

"As if on cue, Hood proceeded to shatter his Army of Tennessee with four near-suicidal attacks on Sherman's well-dug-in positions," explains McManus. Both sides suffered nearly the same number of casualties (more than 30,000), but the loss represented a much higher percentage of the South's numbers than the North. The Confederate army left Atlanta, Lincoln was reelected, and by the spring came surrender.

Lee had warned about gambling producing "deplorable results." And for the South, one might say, Hood's gambling nature had done just that.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America��s Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.

Images: Grant, Lee, Sheridan, Hood photos, public domain; Union Generals Playing Card Deck (Grant) and Confederate Generals Playing Card Deck (Lee), courtesy U.S. Games Systems Inc.

Be sure to complete your PokerNews experience by checking out an overview of our mobile and tablet apps here. Stay on top of the poker world from your phone with our mobile iOS and Android app, or fire up our iPad app on your tablet. You can also update your own chip counts from poker tournaments around ?the world with MyStack on both Android and iOS.