Poker & Pop Culture: Bluffing With Bombs During the Cold War

Many poker players like to say how poker is more than just a game, it's a way of life. Even so, a lot of them probably wouldn't think to claim that poker might have had something to do with life continuing to exist on this planet.

Several years ago, shortly after the publication of James McManus's excellent history of poker, Cowboys Full (2009), I spoke with him about the book. Among the many topics we addressed was the argument his book persuasively puts forth that poker is, in fact, more than "just a game."

When I asked McManus about that, he referenced the significant role poker played during the Cold War when prolonged tension between the United States and the Soviet Union saw each side continuing to develop and build up nuclear arsenals capable of destroying civilization many times over.

"If nuclear stand-offs are resolved by one nuclear-armed leader bluffing another, and the logic of his advisors is based on game theory which is itself based on poker... there's absolutely no way you can think of poker as just a game," McManus explained.

"It has ramifications that go infinitely beyond what happens on the felt with the chips and the money," he continued. "There are tens of millions of lives at stake, and how that drama plays out and crisis is averted occurs as the result of the same logic and psychology that poker players use. And we use the same language �� 'bluff,' 'laydown,' and so on �� to describe both activities. So that, to me, is a knock-down argument for the idea that poker is not just a game."

Let's back up a little to look at the sequence of connections McManus was alluding to �� the ones linking poker, game theory and high-stakes negotiations during the Cold War �� and think a little further about this notion that poker (perhaps) might have already saved us all.

Poker and Game Theory

When McManus referred to advisors drawing on game theory in their recommendations to leaders, he was specifically alluding to Oskar Morgenstern, the German-born economist and mathematician who emigrated to the U.S. during the 1930s and would later serve as an advisor to President Dwight D. Eisenhower during the 1950s.

Morgenstern had been living and working as a professor in Vienna, and in fact it was during a visit to the United States in 1938 that Adolf Hitler took over Austria, prompting Morgenstern to remain in America where he'd eventually join the faculty at Princeton University.

At Princeton, Morgenstern would meet another academic ��migr��, the Hungarian-born mathematician John von Neumann. Back in 1928, von Neumann had published a study in German titled "Zur Theorie der Gesellschafsspiele" or "On the Theory of Parlor Games." Even before meeting von Neumann, his article had been recommended to Morgenstern thanks to the pair's overlapping interests. As the war played out, the pair would subsequently collaborate on a book-length study titled Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944).

The book became a landmark publication, often heralded as having helped establish game theory as a new and distinct scientific discipline. A chapter in the book titled "Poker and Bluffing," based in part on von Neumann's earlier article, helps demonstrate how the study of poker strategy played a role in the development of game theory.

In that chapter, heads-up stud poker is analyzed as one of several "zero-sum two-person games." The authors examine such games as possible models for other, similar kinds of decision-making made in situations where two rational entities oppose one another �� situations that come up, say, in social contexts or in political conflicts or in financial transactions...

Or in war.

You M.A.D., Bro?

Von Neumann also did some advising of presidents. During the war he'd been part of the Manhattan Project that had produced the atomic bombs used in Japan at the conclusion of the war, and was among those advising President Harry Truman about their usage and the choice of targets. In fact, while Morgenstern was later advising Eisenhower, von Neumann was there also providing guidance while serving as the chair of a top secret Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Committee before his death in 1957.

Not long after WWII ended the Cold War began, marked at the start by Winston Churchill's famous "Iron Curtain" speech in 1946 �� a speech that followed a poker game �� and Joseph Stalin's denunciation in response.

During the years that followed the idea of using mathematical models (including some derived from zero-sum games like poker) to describe various types of military conflict began to gain increasing influence. Thinkers like von Neumann Morgenstern were called upon by leaders like Eisenhower to share their knowledge.

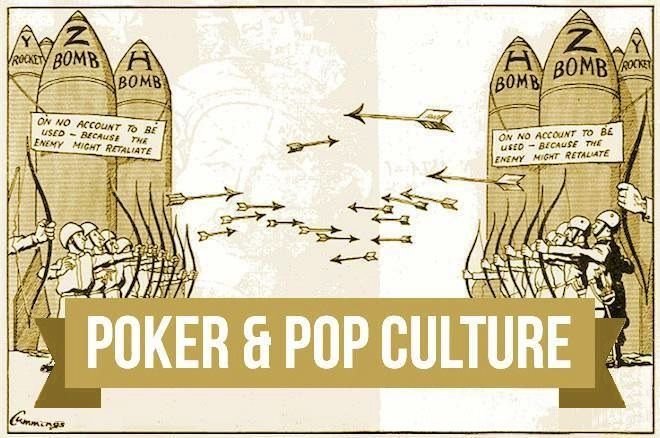

One idea credited to von Neumann that often gets highlighted in discussions of these high-stakes Cold War "games" is the one popularly known as "mutual assured destruction" �� sometimes referred to by its darkly humorous acronym "M.A.D."

The theory was introduced to explain the behavior of two sides engaged in a type of conflict where neither can win without both losing so badly they cannot "play" again. An exchange of nuclear weapons between the two superpowers exemplified such a situation, where neither side could feasibly win in any real sense as both would be utterly destroyed should the "game" begin at all.

Should both sides recognize the reality of the situation (a key component of the theory), both would necessarily avoid engaging in such a conflict �� like a poker player tossing a hand away in a spot where the risk is too great to justify seeking any reward.

Americans Play Poker, Russians Play Chess

Moving into the 1960s and the start of John F. Kennedy's presidency, the Cold War continued to dominate headlines and op-ed pages.

On February 5, 1961 �� just a couple of weeks into JFK's tenure at the top �� Morgenstern wrote an article for The New York Times titled "The Cold War Is Cold Poker" that specifically highlighted the parallel between poker strategy and ongoing diplomatic conflict between America and the Soviet Union.

"The cold war is sometimes compared to a giant chess game between ourselves and the Soviet Union, and Russia's disturbingly frequent successes are sometimes attributed to the national preoccupation with chess," Morgenstern began. "The analogy, however, is quite false, for while chess is a formidable game of almost unbelievable complexity, it lacks salient features of the political and military struggles with which it is compared."

Morgenstern argued that since "chess is the Russian national pastime and poker is ours, we ought to be more skillful than they in applying its precepts to the cold-war struggle." Alas (in his view) that had not been the case by early 1961. Thus did he proceed explicitly to argue in favor of the country's leaders becoming more studious about poker strategy, particularly highlighting the need to learn how bluff effectively (and responsibly) �� and to learn how to recognize the Soviets' bluffs, too.

"The problem of how, on the one hand, to make a threat effective and, on the other, to recognize a genuine threat by your opponent is one of the most fundamental of the day," Morgenstern maintained.

It was an influential argument. By his later actions, Kennedy would get variously credited with having reaffirmed the "we play poker, they play chess" idea, further underscoring both cultural differences and the contrasting strategic approaches of the two superpowers toward each other. And further promoting the "poker provides a better approach" argument as well.

However, not everyone was agreeing with the view that poker was necessarily a better source of Cold War strategy for the U.S. than was chess. A letter to the NYT by Louis Wiznitzer dated three weeks later responded to Morgenstern's article by saying its pro-poker position "sums up pretty much the essential reasons why the United States has been steadily losing the cold war in the last twelve years."

"Whereas the Communists are waging a game of chess, with moves as scientifically planned as possible," noted Wiznitzer, "the Americans are improvising poker moves and bluffs, without a master plan or aim, and depending more or less on their last hand, or reacting to the enemy's bet." Since "politics is not a game nor simply an art" but rather a "science," he insisted, the long-range thinking of chess is actually preferable to the overly reactive game of poker.

"You cannot beat chess with poker," he concluded.

It's an interesting response, and the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion two-and-a-half months later �� soon recognized as a woefully shortsighted "play" with especially damaging consequences for the U.S. �� probably inspired further doubt regarding Morgenstern's argument.

Poker and Diplomacy: Partial Information Games

The later Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 is more often discussed as an application of poker strategy to what was the most tense of all moments during the Cold War. McManus does a nice job applying the poker analogy to that conflict in Cowboys Full, as had David Spanier in his 1977 book Total Poker. Rather than rehearse that complicated conflict and analysis, I'll point you to their discussions of how Kennedy managed to induce Nikita Khrushchev to "fold" and prevent a devasting "showdown."

Like Morgenstern (and others), Spanier noted that "in general, one might say the Russians play chess and the Americans play poker." In his analysis of the crisis, he also supported the idea that poker strategies �� especially the role of bluffing (and recognizing others' bluffs) �� are more obviously applicable to a Cold War staredown in which much that is relevant is hidden from view.

That was Morgenstern's point in his NYT piece. "Chess is, to begin with, a game of complete information," Morgenstern pointed out. "That is, the chess opponent has no unknown cards.... Every move is made in the open; consequently (and this is most important) there is no possibility of bluffing, no opportunity to deceive."

By contrast, he continued, poker "describes better what goes on in political reality where countries with opposing aims and ideals watch each other's every move with unveiled suspicion."

Did poker "save us" during the Cuban Missile Crisis and at other tense moments along the way as the Cold War played out? It most certainly played a role.

Then again, as in poker, luck had a little bit to do with the outcome, too.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America's Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.

Image (top): "Back to Where It All Started," Michael Cummings, Daily Express, August 24, 1953.