Circle of Life, Circle of Death: Depletion and Replenishment in Multi-Table Tournaments

People say that it’s a tough way to make an easy living. I disagree. I think it’s a really tough way to make a tough living.... It’s really, really hard. You have to have the right sort of personality for it, you have to be able to withstand some really, really brutal downswings, and that’s why the majority of the MTT world is backed, because it’s just — the amount of money you really need to play the circuit or play MTTs full-time... most of us are not playing with enough money, that’s true. —Vinnie Pahuja, 2+2 Pokercast (Episode 327)

The poker world — like any world — has its own ecology. Its “Circle of Life,” if you will. But when you flip a Circle of Life around — look at the other side, turn it upside down, whatever — it can look like a Circle of Death, though that wouldn’t have made such a catchy tune for the kids.

Contrary to certain sci-fi movies, there’s no ecology that consists entirely of predators. Inside every shark is a school of fish. Something within an ecology has to die for a predator to thrive, and we can call this process depletion.

For the predator to continue to thrive, however, there has to be a continuous source of food. If the predator runs out of food, it dies, too. The process by which the food source is maintained (however that is done) can be called replenishment.

Winning poker players take some of their winnings out of the poker ecology to buy non-poker stuff to live on, to invest it (if they’re smart), and for other reasons. Casinos take some out as well for rake, to pay dealers, to keep the lights on, and (in some cases) to fight against online poker. Some of that money may eventually come back in the poker ecology, but in the short term, it’s lost. For the poker ecology to maintain or grow, there needs to be an infusion of new money, either from existing players reloading their bankrolls or from new players entering the ecology.

The rapidity at which new players/bankrolls must be replenished is a problem online rooms and small markets (among others) have to calculate. Every pro is familiar with games that “play too big” — that is, games in which money gets sucked from the losing players at a rate where the game’s unsustainable. For a pro, it’s not a problem as long as there’s another game to go to or if their winnings can sustain them until they find another game. But for a business dependent on a local player base or a site that needs to spend money to entice new players, it can spell disaster.

One example of how the depletion/replenishment equation plays out is in the world of the super high roller tournament, a topic that’s been discussed on the PokerNews Podcast https://www.shflgg.com/news/podcast/ in recent months. The number of players who can afford $25,000, $50,000, and $100,000 (or $1,000,000) buy-ins is obviously limited. Events on that scale rarely get more than 50 players. While some players’ pockets are deeper than others’, unless one of them has $10 million socked away, no one has the requisite 100 $100K buy-ins recommended by good bankroll management guidelines.

But as a way of exploring this topic further, let’s say 50 players start off with $1,000,000 each and they all plan to play $100K tournaments until their bankrolls are gone. (For our purposes, it doesn’t matter if it’s their own money or if it’s backing money.) Once they’re broke, the game needs new blood. How much new blood does it need to keep going?

Let’s start with just one tournament:

|

|---|

After a single tournament with payouts for five players (at 41%, 25%, 15%, 11%, and 8%) and a typically low rake for SHRs (3%), the above graph shows how everyone’s bankroll stands afterwards. Most are down by a single buy-in, while the winner of the tournament has nearly tripled his bankroll.

By running a simulation similar to one I used last month for “An Analysis of the ‘Double Bubble’ Payouts Planned for the 2015 PCA” — in this case one showing average results among 50 players without taking relative skill into account — we can project further the effects of depletion and need for replenishment to keep the tournaments running.

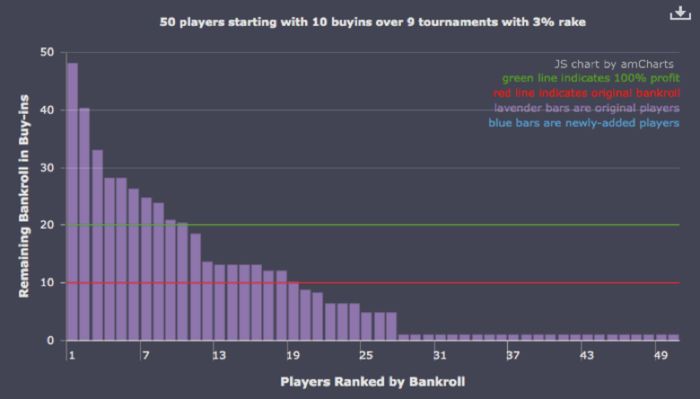

After nine $100K tournaments, then, things will look a little more like this:

|

|---|

(NOTE: Graphs show the results of a single running of the simulation, but numbers quoted are based on multiple runs.)

About a third of the players will not have cashed once in nine tournaments, and will therefore find themselves down to a single buy-in. On average, about 20% of the players will have doubled their bankrolls (or better), and another 15-20% will be profitable with less than 100% increase in their bankroll.

Let’s take it a couple of tournaments further, at which point we have to start talking about replenishment, too...

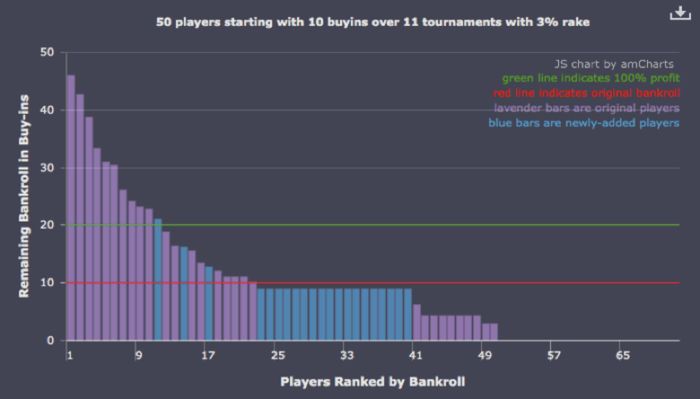

|

|---|

By the 11th tournament, several changes have happened. Most importantly, a little over a third of the original 50 bankrolls have busted. They’ve been replaced by new bankrolls, either reloads or entirely new players. The new players (the blue bars in the graph) will have entered one tournament, and a few will have cashed. About 15% of the original players (7 or 8 out of 50) will have doubled their bankrolls, about 20% of them will have made a lesser profit, with another 30% still in the game but unprofitable.

Let’s play some more...

|

|---|

The 21st tournament is the first in which some of the new bankrolls will be depleted. On average, more than 30 new players/bankrolls will need to be added to keep the game at the same size, making a total of more than 80 players over the course of the 21 tournaments (38% of whom have spent their 10 buy-ins). Again, something more than 15% of the 80 players (now in the range of 13-15) have bankrolls twice their original size, with about the same number sitting between 100% and 200% of their original bankrolls.

|

|---|

After 51 tournaments, more players have gone broke than are playing the game. The number of players with a 100% or greater increase in their bankroll remains steady at 20%. Interestingly, the percentage of players with less than a 100% bankroll increase shrinks to less than 10%, with a slightly larger contingent of unprofitable players who still have a single buy-in.

Meanwhile, about 70% of the original bankrolls (35 of 50) have gone busto. The same is true for almost 60% of the players who first entered (or reentered) between game 11 and game 40. There’s now a constant churn of bankrolls eaten away by buy-ins replaced by newly-minted rolls. Some of the original players seem almost invincible, having increased their bankroll by 500% or 600%.

Now let’s carry this much further and see what happens.

|

|---|

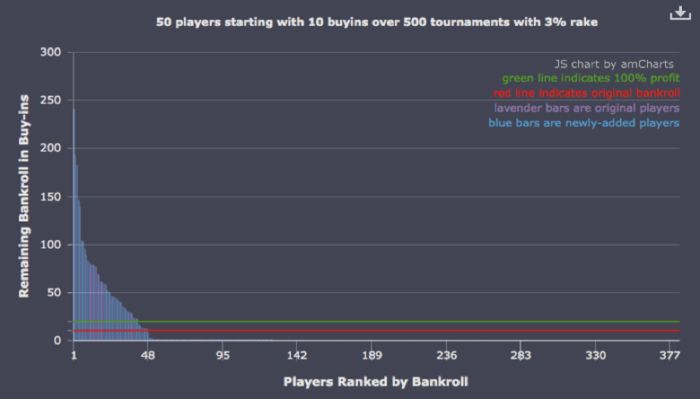

When you extrapolate way out to the far future after 500 similar tournaments have been played — something that might only take a week, if you’re talking about online (and smaller tourneys) — the results are amazing.

More than 330 10-buy-in bankrolls have been depleted. That could be 330+ unique players, 30 players with 100-buy-in-bankrolls, or any combination of about 45 or more players with a total of 3,300 buy-ins. About 40 players — made up of 10% of the original group of 50 with the others new or reloaded players — have doubled their bankrolls (in some cases, several times). If an original player isn’t in that 10% by this point, they’re gone; none of them are in the slightly-profitable or unprofitable-but-still-alive categories. There appears to be a critical mass where their bankroll is self-sustaining or they’re cash-negative. On average, one to one-and-a-half 10-buy-in bankrolls are busted for each game that is played.

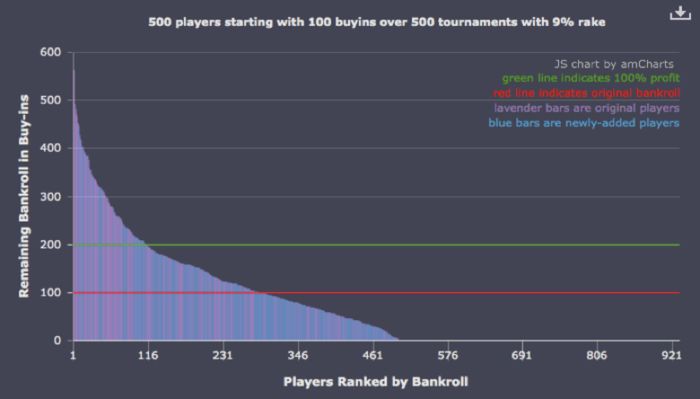

How do things look in a more common situation? How about a 500-player tournament where everyone starts with a 100-buy-in bankroll and the rake is a more common 9% of the total entry cost?

|

|---|

If you run the simulation with these parameters for 500 tournaments, the average number of new players/bankrolls needed for replenishment is 450. In fact, running it for 400, 300, and 200 tournaments, the average number of new players/bankrolls needed for replenishment is, respectively, 350, 250, and 150. In other words, it tracks almost perfectly at 50 new players/bankrolls fewer than the number of tournaments while maintaining a nearly 1:1 relationship of bankrolls chewed up to tournaments.

That’s a not insignificant number of new players/bankrolls needed to maintain the ecology — perhaps more than most realize. Such is the Circle of Life in MTTs — or, perhaps, the Circle of Death.

For those who would like to play around with the simulator and add your own inputs, here it is with an extra variable for considering the percentage of skilled players, too:

Darrel Plant lives in Portland, Oregon. A computer programmer by profession and a game player at heart, he writes about math and poker at his blog, Mutant Poker.

Get all the latest PokerNews updates on your social media outlets. Follow us on Twitter and find us on both Facebook and Google+!